Various authors have suggested the use of different planes to assess the growth direction but I recommend the use of two sequential X-rays superimposed along the ‘SN’ plane at ‘S’ or along the Frankfort Horizontal at the Porion. Alternatively using photographs superimposed on the Tragus along the line from there to the furthest point on the nose. It does not matter much which of these plains are used provided the ‘before’ and ‘after’ superimpositions are along the same lines. The direction of growth is then measured by marking Gnathion or Pogonion on both tracings and drawing a line through them extending to the plain used for the superimposition.

In geometric terms anything less than 45° would be horizontal and anything over would be vertical. 35° to 40° would appear to be close to the functional and aesthetic ideal but there are many nice looking faces and straight teeth associated with angles as high as 50°. Research is difficult on this point as few serial records of outstandingly good looking people are available. However for most severe malocclusions the angle will be over 80°. Some character-full faces are found with high angles but as the growth direction increases there is less and less room available for the teeth. The following two clinical cases confirm the importance of diagnosing maxillary position correctly and the effect of different treatments on the growth direction.

Brian was an eleven year old boy with a class II division 1 malocclusion and an eleven millimetre overjet. He had a convex face with no crowding in the lower and slight spacing in the upper (figure III/13). Faced with an overjet of 11 millimetres and a convex face, most orthodontists would be thinking of some form of retraction but examination of his face shows that his cheeks look rather flat and it will be noticed that he has quite a curvature in his neck suggesting that his head is extended when in his normal position.

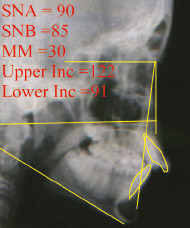

The lateral skull X-ray (fig III/14, left) shows that the SNA is approaching 90° which is considerably higher than most ‘norms’ which are around 82°. Of interest the records of this particular case were sent to every member of the British Orthodontic Society and they all were asked to provide their own prescription. 91% of those who replied suggested that extractions of teeth were required, despite the fact that there was spacing in the upper arch and no crowding in the mandible. 63% recommended retractive head gear and a further 15% thought head gear might be required. However the ‘Indicator Line’ (to be described later) suggested that Brian’s maxilla was several millimetres retruded and if the outline (in blue) of a good looking forward growing face is superimposed on Brian’s cranial vault (fig III/14 right), this would also suggest that the maxilla and upper incisors are too far back

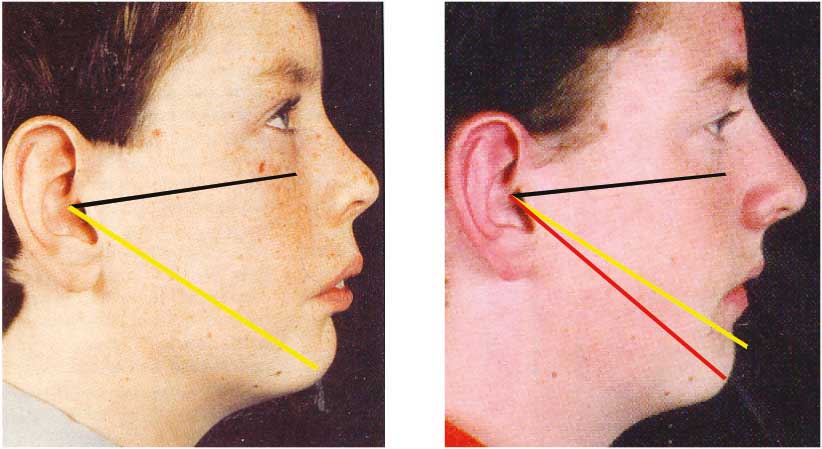

Brian was treated with extractions and head gear to retract his maxilla and the result is shown in figure III/15. A panel of six lay judges thought his facial appearance on a scale from one (very unattractive) to ten (very attractive) had changed from 5.5 before treatment to 4.2 after. Of interest the mandibular growth direction which should be around 55° for an averagely good looking face increased to 112°.

This case was clearly misdiagnosed and mistreated. It reflects a worrying lack of understanding in 1995 amongst the majority of the UK orthodontic specialists about maxillary position and its effect on the mandibular growth. This was probably due to an over reliance on lateral skull X-rays coupled with the use of measurements that do not clearly identify maxillary position.

However if compared with a good looking face, the maxilla and upper incisors are too far back. The SNA is not a safe guide.

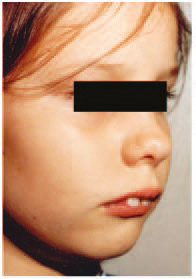

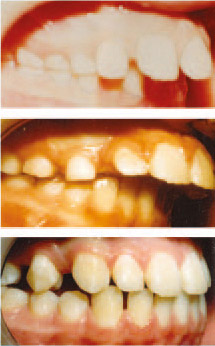

For the sake of comparison let us consider the treatment of a younger girl also with a convex face. Emily is eight years old and has a class II/1 malocclusion with an overjet of 14 millimetres and a complete overbite (fig III/16). Her mother asked for the upper anterior teeth to be retracted. However the Indicator Line (to be described shortly) suggested that they were already too far back and needed moving forward so that the lower jaw could be allowed to come forward as well. Most conventionally trained orthodontists would find this a confusing diagnosis but it serves to illustrate the difference between ‘Orthotropics’ and almost all other approaches.

The precise method of treatment will be described later but was commenced by moving the maxilla and upper incisors forward so that after four months the overjet had increased from 14 to 17 millimetres (fig III/17). This freed the mandible to move forward without interference and she was then trained with appliances to posture into an over jet and overbite of 2mm for twenty two hours a day. Nine months later overjet had reduced to 3½mm and she stopped day-time wear.

Sadly many orthodontic students are trained to believe that changes of this nature can not be achieved with appliances and would explain the result by saying that Emily had a fortunate forward growth spurt, which was pre-programmed in her genetic make up. Others might agree that some of the change was due to the appliances but currently (2018) very few would accept that such changes can be achieved predictably with these methods.

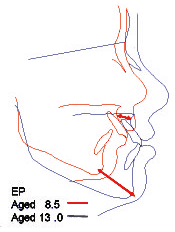

Further information is available from the photographs and X-rays. (Figs III/18, & III/19). The facial improvement is probably due to the growth direction which was 37°. The Bolton study of untreated but probably not ideal patients found a mean growth direction of 54° (Ruf et al 2001). Sadly it is known that most orthodontic treatment tends to increase vertical growth. This is partly because of the eruptive effect of fixed archwires, partly because of the retractive effect of inter-maxillary traction on the maxilla and partly because most appliances are detrimental to oral posture. These factors will all be considered at later points in this book but for the moment let us consider what actually happened to this young girl.

If the X-rays are superimposed on ‘S’ along ‘SN’, it will be seen that ‘A’ point on the Maxilla moved forward about 11mm, while Gnathion advanced 27mm. It may be that such changes have been achieved by other methods but I have never been privileged to see them and personally do not think that any treatment other than Orthotropics could achieve this amount of forward growth. The final growth pattern is much the same as might be expected for any good looking child; the unusual feature is that she started with a vertical growth pattern which changed to horizontal during treatment. It is important to note that no fixed appliances were used at any point.

So what actually happened? I do not believe that a mandible can be made to grow more than a few millimetres although we can certainly change its shape. The upper and lower jaws are linked by a series of bones and we discussed in chapter I the ability of each of these bones to remodel and adjust its relationship with its neighbours. Both Bjork’s (1979) work comparing the growth of Europeans with indigenous Australians and Lobb’s (1987) work with twins demonstrated that large contrasts in the shape and growth of the cranial bones can be achieved by many small changes in relationship rather than form. If each of Emily’s facial bones had moved a millimetre or so relative to its neighbours then the combined movement would have been substantial. Remember that these bones can all rotate, cant and remodel.

What really concerns me is that malocclusions like Brian’s are still being treated in the same retractive manner with long-term damage to the teeth and face. Also the orthotropic treatment given to Emily is still ridiculed and suppressed by many Universities in the United Kingdom. Worse still, the research we need to compare such methods is blocked by even the most respected authorities, so that the public continue to suffer in the hands of those they should be able to trust.